Last week, Trump decided to double down on his campaign to attack Biden’s religious faith, spreading the lie that Democrats refused to say the word “under God ” during the opening of each day’s Democratic Convention invocation. This came just a few weeks after Trump’s outrageous statements that his devout, church-going Catholic opponent was “against God” and that Biden wanted to “hurt the bible.”

Trump’s attacks were similar to, and influenced by, those made 60 years ago by the president’s religious mentor, Norman Vincent Peale, about presidential candidate John F. Kennedy during his 1960 race against Republican candidate Richard Nixon.

Norman Vincent Peale’s controversial “prosperity gospel” formed the altar which Fred Trump brought young Donald and his family to worship. Peale was more than the author of the best-selling book The Power of Positive Thinking and the Trump family minister of the upscale Marble Collegiate Church on Fifth Avenue.

Peale was also a virulent anti-Catholic bigot and first generation “America-firster” who served as the Chairman of a group that evangelist Billy Graham formed in mid-August 1960 called The National Conference of Citizens for Religious Freedom to Oppose Kennedy.

“Faced with the election of a Catholic,” Peale declared at the time, “our culture is at stake.” Peale claimed that Kennedy (our first Catholic president) would serve the pope instead of the American people: “It is inconceivable,” Peale wrote, “that a Roman Catholic president would not be under extreme pressure by the hierarchy of his church to accede to its policies with respect to foreign interests.”

Peale’s position was condemned by former President Harry Truman, the Board of Rabbis, and a number of leading Protestants. Protestant Episcopal Bishop James Pike said, “Any argument which would rule out a Roman Catholic just because he is Roman Catholic is both bigotry and a violation of the constitutional guarantee of no religious test for public office.”

Like Trump, Peale’s power and influence grew despite–or perhaps because of– such widespread notoriety. Religious scholars warned Americans that Peale’s “positive thinking” sermons had little to do with Christianity. Renowned theologian Reinhold Niebuhr argued, “The basic sin of this cult is its egocentricity. It puts ‘self’ instead of the cross at the center of the picture. This new cult is dangerous. Anything which corrupts the gospel hurts Christianity. And it hurts people too. It helps them to feel good while they are evading the real issues of life.”

Yale Divinity School Dean Liston Pope agreed, noting, “There is nothing humble or pious in the view this cult takes of God. God becomes sort of a master psychiatrist who will help you get out of your difficulties. The formulas and the constant reiteration of such themes as “You and God can do anything” are very nearly blasphemous.”

Episcopal Bishop John M. Krumm criticized Peale and the “heretical character” of his teaching on positive thinking, he warned, “The predominant use of impersonal symbols for God is a serious and dangerous invitation to regard man as the center of reality and the Divine Reality as an impersonal power, the use and purpose of which is determined by the man who takes hold of it and employs it as he thinks best.”

For Fred and Donald Trump, Peale’s message fell on welcome ears. In their ethics-barren, Peale-blessed spiritual universe, the Lord helped those who helped themselves. Fred Trump began bringing his family to Peale’s church during the 1950’s and found comfort in their minister’s belief that God’s only interest was in their personal success. Donald and his two sisters were married there, and the president frequently refers to Peale as his life’s formative religious influence.

The core Christian teachings of compassion, forgiveness, acceptance and love–even for those closest to them–were swept aside in favor of Peale’s new gospel of selfishness – and the politics that flowed from it. During the 1930’s, Peale was part of Spiritual Mobilization, a group of politically-active Protestant Ministers backed by powerful oligarchs to oppose FDR’s New Deal policies. The group was soon endorsing a Nazi-sympathizing “America First” movement to oppose the U.S. entry into World War II.

Trump dusted off the America First slogan generations later and made it central to his campaign, appealing to a similar xenophobic, racist, isolationist demographic to vilify and ban immigrants. Pope Francis criticized President Trump’s controversial wall with Mexico in 2016 (and later his family separation policy), observing that, “A person who thinks only about building walls, wherever they may be, and not of building bridges, is not Christian. This is not the Gospel.”

Trump’s response to the pope was, in light of his more recent comments about Biden, illuminating. “For a religious leader to question a person’s faith is disgraceful. No leader, especially a religious leader, should have the right to question another man’s religion or faith.”

In the National Catholic Reporter last month, correspondent Michael White wrote that Biden’s campaign hopes that his “personal story and faith will offer stark moral contrast to Trump.” The article quoted Obama’s former faith outreach chief Michael Wear, explaining, “Donald Trump is someone who needs religion to work for him in order to be politically successful. He is someone who has used religion and religious people. He values them to the extent that they’re valuable to him.” Biden, Wear noted, “isn’t looking to see what faith can do for him. His life has been looking to see how he can serve out of, in part, a motivation of faith.”

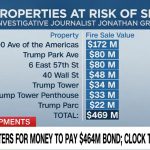

In Donald Trump’s moral universe, Peale’s philosophy of a God whose only concern is helping you win has provided an ethical justification for saying or doing anything to advance his insatiable self-interest. As Mary Trump recently explained in “Too Much and Never Enough: How My Family Created the World’s Most Dangerous Man,” to Donald and his father, “Financial worth was the same as self-worth. The more Fred Trump had, the better he was. If he gave something to someone else, that person would be worth more and he less. He would pass that attitude on to Donald in spades.”

In Donald Trump’s life, Peale’s approach justified behavior so narcissistic that many mental health experts, including his niece Mary, characterize it as sociopathic. Mary’s father, Freddy Trump, spent the last night of his life dying in a hospital bed alone, at the age of 41, because his parents could not be bothered to sit by his side. Donald decided to spend the evening heading out to a movie theater with his wife.

That Donald Trump does not express grief, empathy or compassion the way that most people of all faiths do was more recently evidenced when his younger brother and “best friend” Robert Trump died. After a one hour visit to the hospital Friday, Trump spent his brother’s final hours on earth playing golf with a football celebrity.

Since becoming president, Trump has surrounded himself with prosperity gospel preachers like Paula White, Mark Burns and Darrell Scott. His most influential supporters remain highly influential multi-millionaire megachurch televangelists who believe that God chooses to reward people like themselves, and Donald Trump, with great material wealth.

Leaders of other Christian denominations take a far more critical view of Trump’s priorities, and his use of religion as a tool to advance his political power. On June 1, after Trump ordered police to forcibly clear a peaceful Black Lives Matter protest using flash grenades and tear gas so that he could stage a photo op at St. John’s Episcopal Church, horrified clergy were forcibly removed so that their church could be used as a prop.

Within hours, Michael Curry, the Presiding Bishop of the Episcopal Church in the United States criticized Trump’s misuse of “a church building and the Holy Bible for partisan political purposes… in a time of deep hurt and pain in our country. The Episcopal bishop of Washington, Rev. Mariann Budde, went further, decrying Trump for holding up a Bible which “declares that God is love,” while “Everything he has said and done is to inflame violence. We need moral leadership, and he’s done everything to divide us.”

The next day, Trump continued his political tour of D.C. churches with a visit to the Saint John Paul II National Shrine in Northeast Washington. D.C.’s Catholic Archbishop Wilton Gregory protested, saying “I find it baffling and reprehensible that any Catholic facility would allow itself to be so egregiously misused and manipulated in a fashion that violates our religious principles, which call us to defend the rights of all people, even those with whom we might disagree.”

Were he alive today, Trump’s religious mentor Norman Vincent Peale, would have had no such concerns. When asked, a few decades ago, about his most controversial congregant, Peale described Donald Trump as “kindly and courteous” with “a streak of honest humility.”